Technical Information

(and more)

Triumph

Spitfire Performance Enhancements (August

2014 edition)

Why

bother improving Spitfire performance?

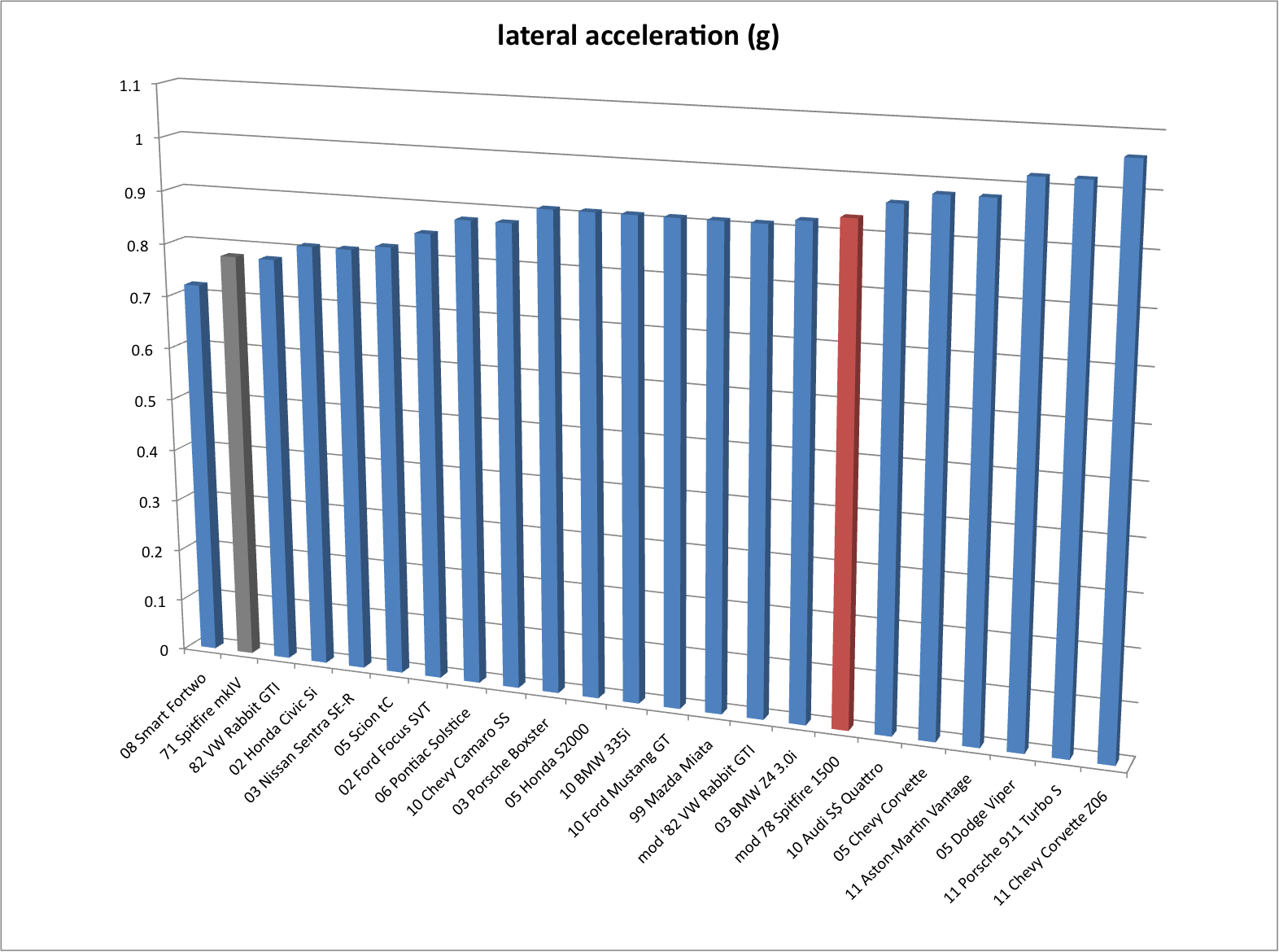

Triumph Spitfires are basically fun, economical street-legal go-carts. Many are still around (more than 300,000 were manufactured from 1962 to 1980), they are simple and easy to work on, and parts are relatively inexpensive and readily available. The later model Spitfire is not a bad-handling car in factory spec. It bested its contemporaries in handling and it holds its own even now. However, some simple changes and upgrades, especially to the early Spitfires, can significantly improve handling and enhance safety. Power, acceleration and speed are where the Spitfire was mediocre in its day, and by today's standards it's underwhelming. But here again, a few simple, relatively inexpensive and easy changes can yield significant improvement, and by putting it all together you will have a much more fun car. The following article is a brief summary and represents my own observations and findings for putting together a fun, reliable and safe Spitfire that can be used with confidence on the street for years and years.

This article is aimed at improving Spitfire performance for sporty

street use at reasonable cost. It’s not a race car

preparation

guide,

although the physics is universal and many of the specific enhancements

apply to both street and track use.

There are several good race preparation guides for Spitfires written by

people with experience building and racing Spitfires. These include the

Triumph Race Prep Manuals, Kas Kastner's race prep guidelines and Jon

Wolfe's "A Guide To Racing Your Triumph Spitfire or GT6." Furthermore,

I’ve limited the scope of enhancements herein to things that

keep a

Spitfire a Spitfire—or at least a Triumph for the most

part—and do not

go into things like radical

engine swaps or drivetrain transformations

(notwithstanding how fascinating, fun and exciting they can be). This

article is meant to benefit Spitfire enthusiasts who want to reliably

use their Spitfires often, improve their performance and derive more

enjoyment from them without having to go to extremes. I attempt

throughout to explain "why"—the

principles

behind the improvements—followed by "what"—the

specific improvements

themselves—to promote understanding and foster creativity.

More

in-depth information can be found in references cited

throughout the article. Exact details of “how” to

implement the

improvements are more the realm of shop manuals and so "how-to"

information is not covered in great detail here. This article is

divided into two main sections—Handling and

Power—and in each section,

the enhancements are listed serially in rough logical order. However,

like any engineered assembly, the Spitfire is a system. Changes involve

trade-offs and often these changes need

to be considered in the context of the

whole vehicle and executed in concert. I hope you

find

this information helpful.

HANDLING

Suspension Basics

Weight

Alignment

Wheels and Tires

Wheel Studs

Front Suspension

Rear Suspension

Anti-Roll Bars

Dampers

Bushings

Brakes

POWER

Torque and Power

Gearing

Weight

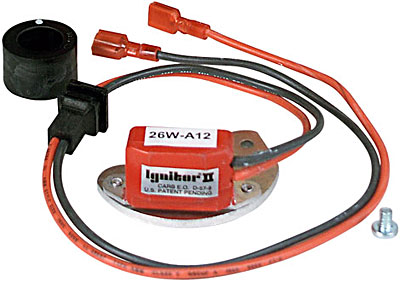

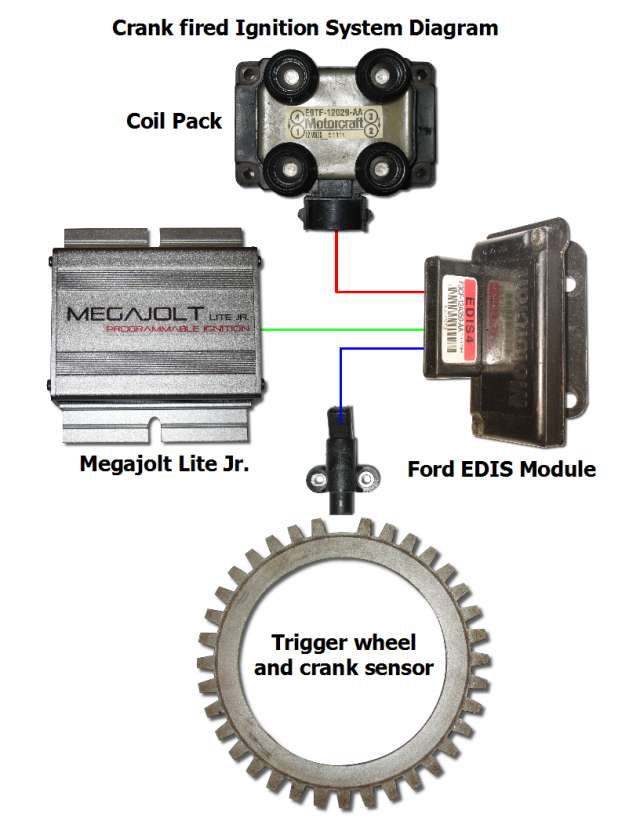

Ignition

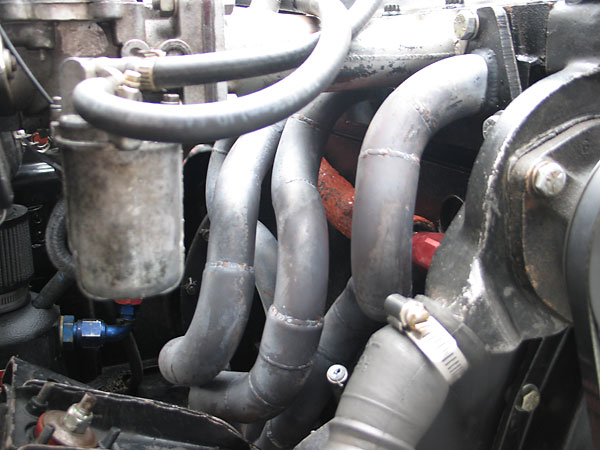

Exhaust

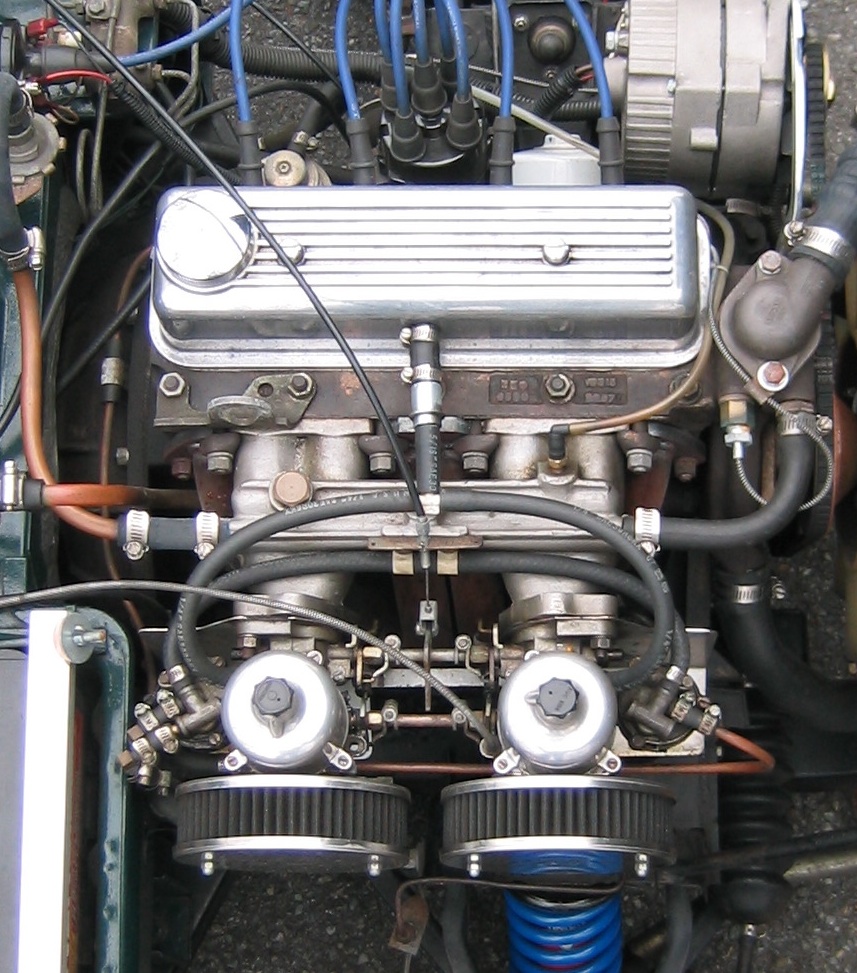

Intake

Cylinder Head

Compression

Camshaft

Machining Tolerances

Bottom End

"Spit-6"

Fuel Injection

Forced Induction

Other

Understand Some Suspension Basics

The

main purpose of the suspension is to ensure proper positioning of the

tires relative to the road for good grip, despite bumps, dips and

cornering forces, to enable safer and faster handling. The entire

suspension--tires, wheels, linkage, springs and dampers (shock

absorbers)--and the overall rigidity and mass properties of the

vehicle are a system that should be considered as a whole when making

changes to any of the individual elements. The mass of the vehicle and

how it is distributed, the geometry of the suspension elements and the

stiffness of the springs and the damping coefficients of the damping

elements determine how much and how quickly the vehicle will roll,

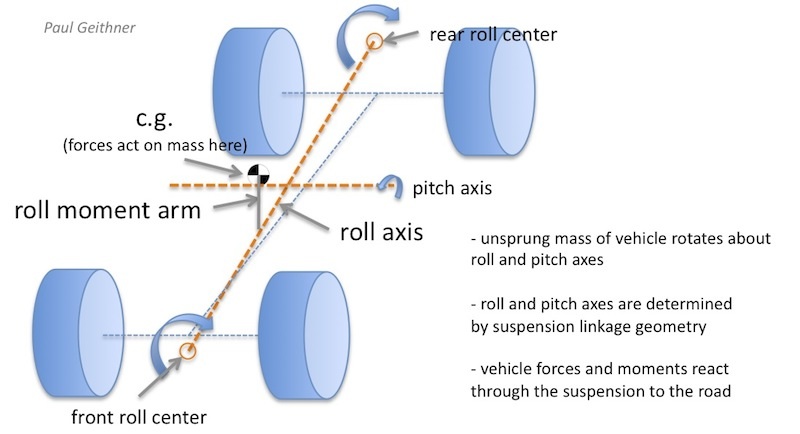

pitch and yaw in reaction to gravity and handling forces.

At any given point in time with any given set of forces, weight is

being transferred through the suspension to the ground, and the key

principle behind suspension tuning is that the load path with the most

stiffness will transfer the most weight. If more force is

transferred

through a given tire than it can handle, exceeding it's ability to

adhere to the road, then it will lose grip and slide, and control will

be relinquished. If the front of the vehicle slides first, it's called

understeer (or pushing, or plowing), and if the rear of the vehicle

slides first, it's called oversteer (or getting loose or fishtailing).

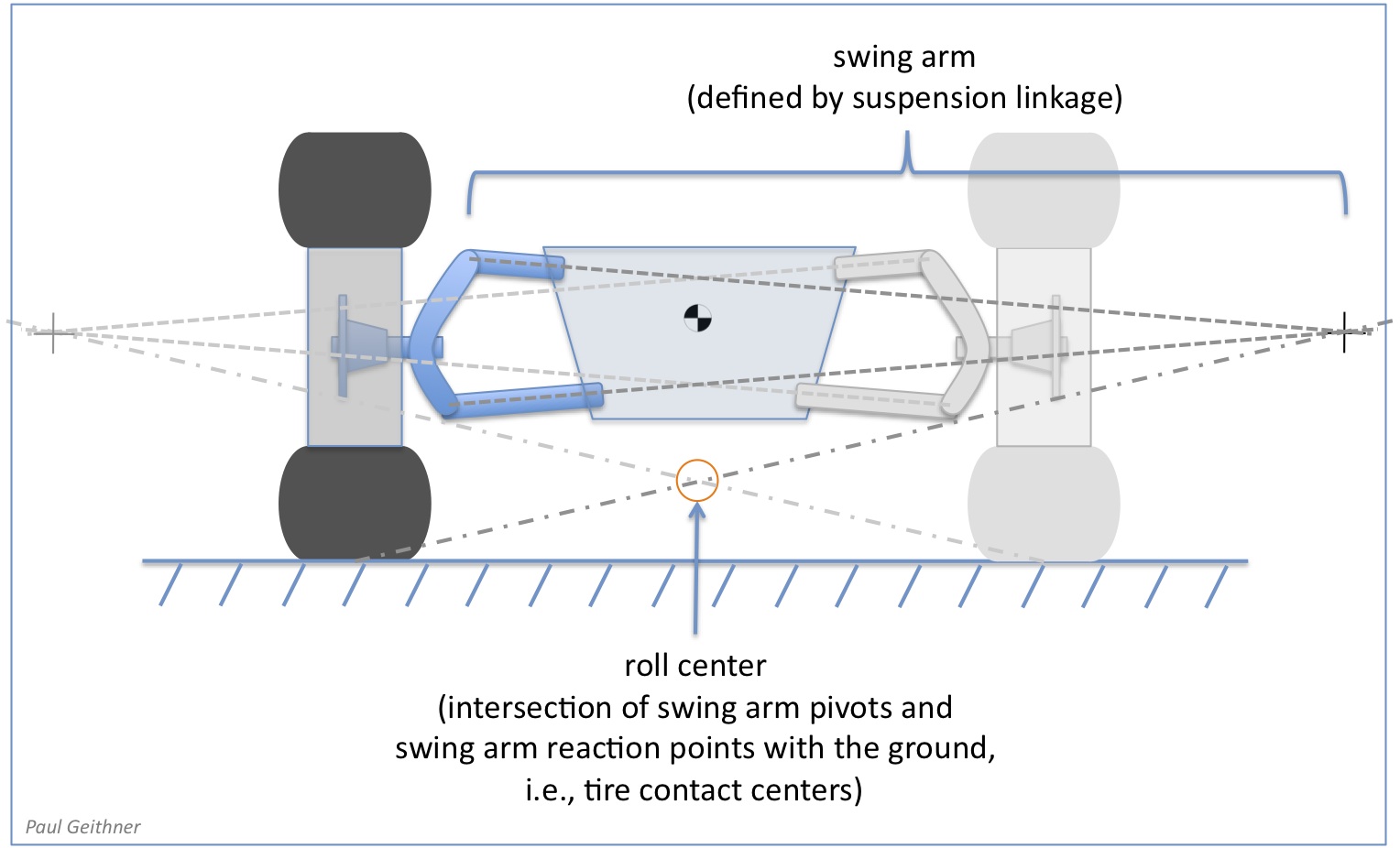

The objective of performance suspension tuning is to manage weight

transfer, enabling higher cornering and acceleration/braking forces

while staying within the limits of tire adhesion. This is done

primarily by managing mass, the height of the center of mass (a.k.a.

center of gravity, or c.g.), and the length of the moment arms that

forces on the c.g. react through to reach the ground by managing the

geometry of the suspension linkage, and by setting the compliance of

the suspension by managing the geometry of the suspension linkage and

the stiffness of springs and dampers. Generally, the following are good

things for handling: less mass, more concentrated mass (i.e., lower

polar moment of inertia), lower c.g., shorter distances between mass

centers and roll centers (i.e., shorter moment arms—good for

reducing lateral weight transfer due to body roll of sprung mass),

lower roll centers, wider track, and longer wheelbase. These may sound

simple but their implementations sometimes work against each other and

other objectives of vehicle design, and entail various costs and

disadvantages, so suspension solutions are many and varied.

What

ultimately matters here are the forces where the rubber literally meets

the road, i.e., the forces of the accelerating mass of the car versus

the reaction forces of the ground. Wheel rates, which are the product

of spring rates and the leverage and motion of the suspension, are the

actual rates of vehicle stiffness. Simply adding wheel rate

contributions from individual suspension elements yields total wheel

rates and vehicle stiffness. Spring rates alone mean nothing as a

measure of vehicle stiffness and they can be very misleading--it is

wheel rates that matter. I've

tabulated various factory and aftermarket front coil, front anti-roll

bar (ARB) and rear leaf spring

rates

and resultant wheel rates and roll stiffnesses for

nominal Spitfires and GT6s.

Lose

Weight, i.e., "Add Lightness"

All

else being the same, a lighter car will out-handle a heavy one.

Trimming weight is easy to do on the later U.S. market Spitfires by

removing all the extra bumper and bumper reinforcing hardware they were

burdened with. This light weighting will not only make the car less

massive, it will eliminate weight at the ends of the vehicle, thus

reducing its polar moment of inertia, meaning it will be easier to

start and

stop it turning. Moreover, many people think this conversion to the

European spec look or pre-1974 U.S spec look improves the car's

appearance. Best of all, it's free. There are other ways to

“add

lightness” such as replacing various bits and pieces with

lighter ones.

Weight reduction boosts performance, and every little bit counts.

Before discussing the following changes to the front and rear suspension, it is important to review alignment. There are six spatial degrees of freedom: translation along and rotation about each of three spatial axes. The three most basic alignment measures are Caster, Camber and Toe, and they are critical to handling, tire wear and safety. Changes to the suspension will result in changes in alignment that need to be measured and adjusted.

On the Spitfire, caster, camber and toe can be adjusted at the front

reasonably easily. The Spitfire front suspension is a

classic unequal A-arm design. Caster and camber can be adjusted

using shims between the lower A-arms and the frame rails. Addition of

shims adds negative camber. Adding or subtracting unequal numbers of

shims between the front

and rear A-arm interfaces changes caster (more shims at the aft

mounting

adds positive caster). Adjusting the tie rods sets toe.

Note that because of the tie rod geometry, Spitfires exhibit a

significant amount of toe change with up and down (bump and droop)

suspension motion, called bump steer. Therefore, when changing camber

and caster, toe must be checked and reset, and toe should be adjusted

last.

At the rear of the Spitfire is a swing axle architecture with a single

transverse leaf spring. The swing axles themselves are the

primary suspension links; the transverse

leaf spring and trailing radius arms guide the swing axles up and down

and

locate them fore and aft.

Rear caster is for all practical purposes not adjustable, camber

is determined by rear ride height (an intrinsic feature of the swing

axle design), but toe is adjustable using shims where the radius arms

interface with the vehicle

tub. After achieving final ride height and hence rear camber, toe

should be measured and then adjusted if necessary (rear toe changes

much less than front toe).

Stock alignment specs vary across models and can be found in

shop manuals. Specific non-stock settings are mentioned during the

subsequent discussion of suspension mods. Overview information on

generic

alignment metrology and the effects of alignment can be found

in the

following primer:

A Short Course on Wheel Alignment

Install

Better Tires and Wheels

The

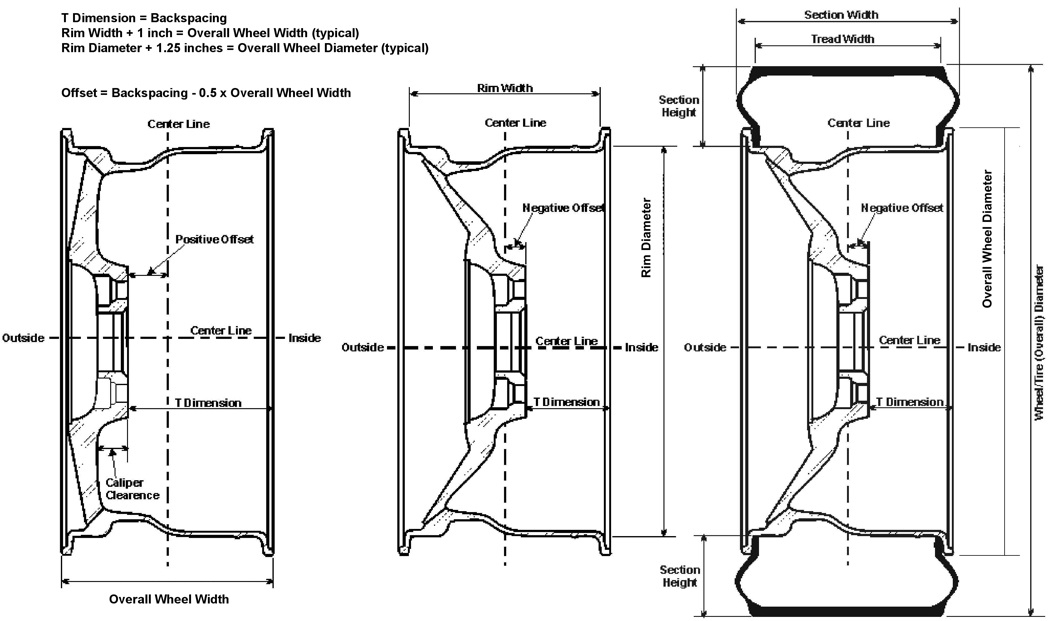

use of even

wider

wheels and tires is

possible, but selection of the proper wheel offset is critical for

avoiding interference

between the

tires and the car's bodywork or suspension elements.

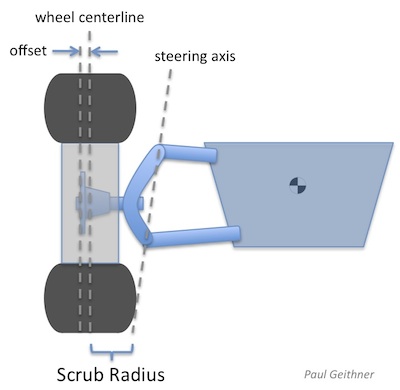

Moreover, offset combined with the steering axis, rim width, camber and

overall wheel/tire

diameter determines scrub

radius, which is the distance between the steering axis and

the

centerline of the tire at the ground (on the Spitfire, the steering

axis is the line that goes through the center of the vertical link ball

joint and trunnion; stock Spitfires have positive scrub radius).

Minimizing scrub radius will distribute loads better

on

the wheel bearings, help enable good tracking and

straight-line braking (i.e., help minimize pull to one side or the

other), make steering easy and help minimize tire wear.

There are wheel and tire fitment procedures you can follow to check and see by direct measurement what wheel and tire combinations ought to fit your car. When there is rubbing on a Spitfire, it typically occurs at the inner edges of the front fender lips during up and down suspension motion and at the firewall just aft of the front tires during turns. Too much width and/or not enough offset is usually the root of the problem. Other rub areas can be at the rear radius arms and rear fenders. Generally, using tires wider than 185mm and bigger than 22 inches in overall diameter requires rolling or folding-up of the inner edges of the front fenders, especially if the vehicle has been lowered. Of course, if you do body work to flare the fenders, you can build-to-suit and avoid rubbing the fenders this way and expand the range of wheels and tires even more.

Note that ever-larger wheels and lower profile tires are not

necessarily better. Bigger diameter rims and tires are typically

heavier, so they add unsprung weight. Moreover, their mass is

distributed at a larger radius from the hub so they have more

rotational inertia and so they are more difficult to start and stop

rotating. Lower aspect ratio tires are less compliant, so they may not

be matched to the rest of the suspension. Given the large amount of

rear camber change that Spitfires exhibit, a moderate profile tire with

some compliance is best for grip. Besides, very low aspect tires leave

the wheels more susceptible to damage from objects and potholes in the

road. Lastly, be sure that the wheels won't interfere with the front

brake calipers. Virtually all 13 inch wheel options will work with

stock Spitfire Girling 12 calipers (mk1 and mk2) and Girling 14

calipers (mk3, mkIV and 1500), but TR7 wheels interfere with the larger

Girling 16 calipers for the GT6 due to their offset (see brake upgrades

later in this article).

Install Thicker, Longer Wheel Studs

Something to seriously consider, especially when using alloy rims, is to upgrade from the stock 3/8 inch, 24 threads per inch wheel studs to ones that are thicker, longer and stronger. Being as thin as the stock studs are, they are susceptible to over-torquing, and being as old as many are, they likely have been over torqued by someone in the past. Fitting wider wheels with wider, stickier tires allows the car to generate more cornering force, which puts more stress on the studs. Furthermore, alloy rims have thicker center sections than steel ones, and so the lug nuts engage fewer threads, making a somewhat marginal situation even more so. Upgrading to 7/16 inch or 12mm studs that are longer than the stock Spitfire/GT6 ones is good insurance, and a really good idea if you are considering driving your Spitfire sportingly. One very good solution is to upgrade to Land Rover Freelander studs (part number CLP9037L). These are 12mm thick, 1.5mm per thread (i.e., M12x1.5) and are 2 inches long, 1 1/4 inches of which is threaded, versus the stock studs that are 1.5 inches long, 3/4 inches of which is threaded. The comparison photo below clearly illustrates the dramatic difference.

For more details, see Upgrading

Triumph Spitfire Wheel Studs.

Changing wheel alignment and lowering and stiffening the Spitfire can improve handling. Lowering brings the c.g. and roll centers closer to the ground, which helps reduce jacking and roll in turns, which helps maintain proper suspension geometry during turns, which keeps the tires in proper contact with the road so they can grip, which enables faster speeds through turns. Similarly, some suspension geometry changes and stiffening can reduce pitch (i.e., dive during braking and squat during acceleration) and limit bump steer. Stiffening helps by limiting the amount of roll and suspension geometry change for a given amount of acceleration. Moreover, stiffer springs reduce the amount of travel for a given load to offset the loss of bump travel due to lowering.

Some

lowering and stiffening is good, but too much makes things worse. Too

much lowering generates poor suspension geometry that lowers the roll

center too much, thereby lengthening the lever arm between the roll

center and the c.g. to increase the roll moment that increases lateral

weight transfer due to body roll and increases changes in suspension

geometry to actually make

handling worse (note however that simply reducing overall wheel/tire

diameter beneficially lowers the c.g. and roll centers without changing

the linkage geometry). Moreover, too much lowering leaves inadequate

ground

clearance for everyday use. Too much stiffness actually reduces grip

and makes for an uncomfortable ride. Too much change in stiffness at

one end of the car relative to the other, or stiffness not matched to

the static weight distribution of the car, will lead to excessive

understeer or oversteer. The right amount of lowering and stiffening

can optimize the geometry of the suspension links so that the car

transfers less weight for a given amount of roll, as well as rolls less

in response to a given set of forces to help maintain better tire

geometry for good grip.

A good compromise static front suspension geometry for a stiffened Spitfire at rest on level ground is when the lower A-arms are parallel to the ground. This is a reasonable compromise that lowers both the c.g. and the roll center without increasing the roll moment too much. This geometry occurs when the total distance between the center of the bolt attaching the damper to the lower A-arm and the upper spring seat is 10.25 inches. Because the distance from the lower A-arm to damper (shock absorber) connection and the bottom spring seat is nominally 3.25 inches, this also corresponds to a compressed length of the front coil springs installed of 7 inches.

Ways to lower the front include 1) shortening the stock springs, 2) replacing the stock springs with shorter ones and 3) installing front dampers (shock absorbers) that have adjustable height spring seats. Dampers with adjustable spring seats allow fine adjustment of static ride height and provide the most flexibility, but fixed seat dampers will yield the desired ride height if used with springs that have the right combination of stiffness and free length. Stiffer springs reduce the amount of travel for a given load, thereby helping to offset the loss of bump travel due to lowering. The least expensive way to lower the front is to simply cut one free coil off one end of each of the stock springs. This shortens and slightly stiffens the springs, and the pigtail left by this operation will compress and not be an issue once installed in the car. On the Spitfire 1500, this will result in the desired installed static coil length of about 7 inches. Another option is to cut about half a free coil off one end of each spring and then heat and carefully reform and flatten the cut ends. However, this is not easy to do correctly. The application of too much heat can ruin the temper of the springs, and getting two springs to come out the same is difficult and not guaranteed. In either case, this shortening of the stock springs will stiffen them only marginally (about 10 percent). While additional stiffness is good because it limits suspension travel and helps offset the loss of bump travel that comes with lowering, such a marginal increase is not enough. Another approach for the Spitfire 1500 is to install springs from a Spitfire mk3 or mkIV. These springs are shorter in free length but also softer than stock 1500 ones, and using them on a 1500 will lower the front end and result in an installed spring length of about 7¼ inches. Softening while lowering is bad though because the need for suspension travel is increased at the same time the amount of bump travel is reduced, thus greatly increasing the likelihood of bottoming-out the suspension. Therefore, using softer springs like those from an earlier model Spitfire on a 1500 is not recommended. Running out of suspension travel and hitting the bump stops is harsh, leads to sudden understeer and can cause loss of control and is potentially damaging. Replacement springs need to be stiff enough to be compatible with the reduction in bump travel but not so stiff as to make handling worse, so the right approach is to replace the stock springs with shorter and stiffer ones that have the right combination of stiffness and free length. I've developed a spring calculator that determines which combinations of spring stiffnesses and free lengths produce the targeted installed spring length of 7 inches on Spitfires and GT6's. Solutions from this calculator and good choices for sporty road going Spitfires are 350 pound per inch, 9 inch free length coil springs for the 1500, 325 pound per inch, 9 inch free length ones for the mkIV and 300 pound per inch, 9 inch free length springs for the lighter mk3 and earlier Spitfires. Compare these with the popular aftermarket "lowering" springs for Spitfires that are 330 pounds per inch, 9.2 inches free length. A good choice for GT6's with their added mass and additional front weight bias are 400 pound per inch, 9 inch free length springs. Such 2.5 inch inside diameter coils springs are available from a multitude of vendors. Below are profile photos of my 1978 Spitfire 1500 with 350 pound per inch, 9 inch free length springs and my 1968 Spitfire mk3 with 300 pound per inch, 9 inch free length springs. These front springs help result in much improved handling, and form follows function with an attractive, level and purposeful stance.

When

lowering, ensure that enough suspension travel remains in bump.

Lowering the car as described above

will reduce bump travel by about half, leaving approximately 0.75

inches between the top of most replacement dampers and the elastic bump stops installed

on them. However, due to the geometry of the front suspension, this

translates into about twice as much travel at the tire, or about 1.5

inches. The

spring rates called out above are approximately twice the stock factory

spring rates and therefore are compatible with, and effectively

compensate for, the factor of two reduction in bump travel. If more

bump travel is desired or needed, some minor trimming (up

to 3/8 inch, or 1 cm) of

the

bump stops is typically possible, but the best approach is to use short

bodied dampers. This trades some of the surplus droop travel resulting

from lowering for more bump travel. Additional bump travel is good in a

lowered car, especially if the car will be

driven to its limits of cornering ability (e.g., autocross). Although

short bodied dampers can have less total travel than standard length

ones, a stiffer setup does not require as much. Good

short bodied front dampers for lowered small chassis Triumphs

are ones that fit the Ford Mustang II, like from QA1 and Pro Shocks. See more information in the section below on dampers.

One thing that lowering the front will also do is to push the camber of the front wheels toward the negative. An otherwise stock Spitfire will end up at around 1 degrees of initial negative front camber due to the lowering described above (i.e., with the lower A-arms are parallel to the ground at rest). Some amount of initial negative camber at the front is desirable in that it aids entry into turns. Motion toward additional negative camber is generated during cornering by the motion of the unequal length and non-parallel A-arms and rotation of the steering axis with positive caster. This helps offset the motion toward positive camber due to roll during cornering such that the net result is to square the tire with the ground for optimal contact and grip. A minor amount of initial negative camber like 1 degree at the front of a lowered and stiffened Spitfire can benefit handling without causing excessive or uneven tire wear or severely reducing straight-line braking distance.

As

mentioned previously, front toe

will be changed significantly by lowering, so toe must be measured and

reset. 1/16 inch front toe-in as prescribed in

the

repair manuals is a good setting for all-around street use. I've developed a simple,

quick and

inexpensive way to make your own toe

adjustments. Bump steer, which is the change in

toe and steering behavior due to up and down motion of the suspension,

is an

unfortunate feature

of the Spitfire, and lowering the front suspension exacerbates it by

increasing the angle of the steering tie rods. While bump

steer is acceptable with the aforementioned changes, shimming the

steering rack to raise it (if possible without interfering with the

crank pulley of the engine) can compensate some by making the

steering tie rods more horizontal at rest.

Note

that stiffening the front of a vehicle means more weight

transfer occurs at the front, which typically increases

understeer (everything else being equal), but the improved geometry

gained from

the lowering and stiffening described above largely offsets this and

the net

result is a car

that

handles much better.

The Spitfire rear suspension is a swing axle architecture. Much maligned and archaic today, some celebrated high-performance cars of the past like the "Gullwing" Mercedes-Benz 300SL of the 1950's and the Auto Union race cars of the 1930's employed swing axles. On the Spitfire, the transverse leaf spring and trailing radius arms connect to the swing axles via pivoting vertical links to locate the swing axles fore and aft. The swing axle suspension has the advantages of independence, simplicity, low cost and low unsprung weight, but it has the disadvantage of poor camber control and potentially dangerous handling behavior. The defining characteristic of swing axles is that the axle shafts are coaxial with the hubs and so the shafts are normal (plane perpendicular) to the wheels. There is only one articulating joint, which is the u-joint at the differential. Swing axles serve as both driveshafts and primary suspension links, and because swing axles themselves are the suspension swing arms, which are short, the design has a high rate of camber change. The roll center is particularly high and thus prone to “jacking," which is progressive raising of the car due to both braking and turning forces. During a turn, if the outboard swing axle (which is taking most of the load during the turn) angles up toward the differential (which is sprung weight attached to the chassis), then turning force transmitted to the sprung mass has a component pointing up that raises the rear end of the car, i.e., the axle helps to push the rear of the car up even higher. As the effect progresses, it gets worse and worse, camber gets more and more positive and grip becomes less and less. Quickly, grip is reduced to the point that the rear tires break loose and the car goes into violent oversteer.

Reducing

or precluding

jacking and

controlling

rear camber change are

paramount objectives of swing axle control. Methods

include lowering the rear/adding negative camber, reducing

roll stiffness while increasing droop stiffness, and lengthening the

swing axles.

Swing Axle Ride Height

and Camber

Camber of swing axles is solely determined by the height of the

differential relative to the hubs and the length of the swing axles.

Because the differential is sprung

mass attached to the chassis, this means rear camber of a given set of

swing axles is determined by

rear ride height. Lowering the rear generates negative camber; raising

the rear generates positive camber. Initial negative camber on swing

axles helps two ways. First, it lowers the rear c.g. and roll center,

which reduces jacking during braking and turning. Second, it

"pronates" the swing axles, angling them so the ends at the

differential are lower than the ends at the wheels, which means that

during a turn, the rear of the car has to rise and roll more before the

angle of the outboard axle points up toward the differential (i.e.,

assumes positive camber) to add more jacking force.

The simplest, most straightforward way to lower the rear is to use a shim in between the differential and the transverse leaf spring. Since the differential is attached to the chassis and is located below the transverse leaf spring, a Spitfire rear literally hangs from its transverse leaf spring, and so adding a shim (a.k.a. "lowering block") between the spring and the differential lowers the rear of the car.

While some initial negative rear camber is good, too much prohibits formation of good tire contact (especially with wider, lower-profile tires), reduces tracking stability, degrades braking and causes uneven tire wear. Experience suggests that compromising at 3 to 4 degrees initial/static negative rear camber is good for the sporty street Spitfire.

Roughly speaking, each 1/4 inch of lowering block thickness generates nearly one degree of negative camber change. For example, if you are starting with -1 degrees and you want to achieve -4 degrees, that's a -3 degree change and so a 3/4 inch block will do. Knowing that 1/4 inch of block thickness generates nearly one degree of negative camber change is handy because commercially-available lowering blocks come in 1/2, 3/4 and 1 inch thicknesses, corresponding to almost 2, 3 and 4 degrees of negative camber change, respectively. You can zero in on other change values if you machine your own block. Be aware that the use of any lowering block thicker than 0.5 inches net will necessitate using longer studs to attach the transverse leaf spring to the differential, which in turn may require modification of the spring/differential access cover to provide clearance for the longer studs. For more details on lowering blocks, including a drawing of a lowering block so you can machine your own, see my Triumph Spitfire & GT6 Lowering Block page.

On my '78 1500, after I modified the front suspension, I had just over 2 degrees of negative camber at the rear and a slight rake overall (front lower than the rear). I fabricated and installed a 0.45 inch thick lowering block (machined from 5/8 inch thick 6061 T6 aluminum plate) to produce a total of 4 degrees of negative camber at the rear and eliminate the rake. The lower rear roll center and c.g. and added negative camber has resulted in quite noticeable handling improvement--reduced jacking with no light feeling from the rear, and reduced roll during cornering--and more driving confidence and enjoyment.

As with lowering the front, ensure that enough suspension travel remains before the bump stops on the rear dampers come into play. Be sure that your dampers (shock absorbers) have adequate travel such that the rear of the car does not contact the bump stops at rest or while driving (except for the occasional pothole or something else extreme, in which case the bump stops provide protection). Each inch of rear damper travel on a Spitfire translates into 1.6 to 1.8 inches of wheel and tire travel. Go for a minimum of one inch of damper bump travel from rest. For extra bump travel after lowering lowering the rear, consider shorter bodied dampers like those from Pro Shocks and Spax. See more information in the section below on dampers.

Rear Stiffness

Increasing bump and droop (vertical) stiffness reduces the rate of camber change and hence limits the total amount of camber change for a given load, which is good for swing axles. However, reducing rear roll stiffness reduces rear lateral weight transfer, which suppresses jacking (as well helps prevent the inside rear tire from unloading enough to lose grip and spin, thus robbing drive torque from the loaded outside tire). So, reducing the roll stiffness of a swing axle rear is good too. The problem is that with a conventional spring, these are competing objectives; increasing vertical stiffness increases roll stiffness, but reducing roll stiffness requires reducing vertical stiffness. Engineers at Standard-Triumph simultaneously increased vertical stiffness and reduced roll stiffness with the innovation of the "swing" spring. The factory switched from the "fixed" spring to the swing spring in the later Spitfires and GT6s (all mkIV and 1500 Spitfires have a swing spring, as do GT6 mk3s from KE/KF20001 onward). The trick of the swing spring design is that only the bottom leaf is actually affixed to the differential while the rest float and pivot, or "swing" to a limited degree about a center bushing. Roll stiffness for small, practicable angles is reduced significantly because only the fixed leaf contributes wholly to roll stiffness, while vertical stiffness is increased substantially because all the leaves participate in vertical stiffness and they are thick such that swing springs provide greater overall vertical stiffness than the fixed springs they replaced (~320 lbs/inch vertical stiffness for the Spitfire swing spring vs. <170 lbs/inch for the Spitfire fixed spring). For complete comparisons, including wheel rates, see this table of spring parameters.

Update to the Swing Spring

In the case of the early fixed spring Spitfires, it is a good idea to update the design by replacing the fixed spring with a swing spring. The higher vertical stiffness and lower roll stiffness of the swing springs of the mkIV and 1500 Spitfires and late GT6 mk3 works well to suppress jacking and consequential extreme positive camber and loss of grip during braking and cornering, as noted in numerous road tests from the era and as indicated in this photo from a 1971 road test of a Spitfire mkIV:

This is a bolt-on change. The swing spring pivot box is attached to the differential housing with only four studs instead of six for the fixed spring, so when making the change you should plug the the two unused middle stud holes in the differential housing. Note that with fitment of the swing spring, the front anti-roll bar (ARB) should be replaced with a stiffer (thicker) one--just as Standard-Triumph did--to restore the net loss in total vehicle roll stiffness (more on anti-roll bars shortly). Canley Classics sells a swing spring conversion kit that includes a swing spring, the stiffer late model ARB and all necessary hardware to make the switch. Alternatively, you can source your own swing spring and stiffer ARB hardware from new or salvage parts.

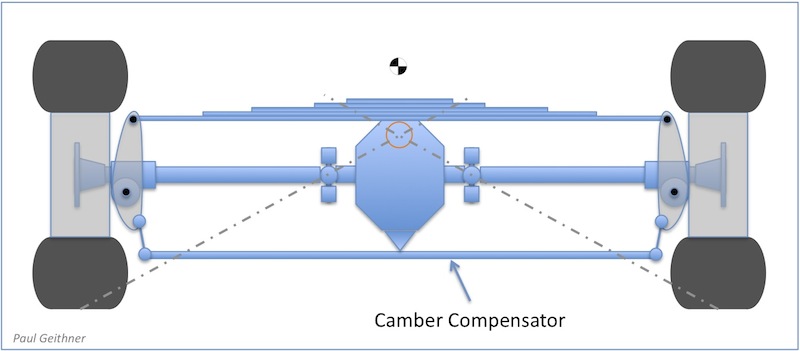

The “Camber Compensator”

Recall that increasing vertical stiffness without adding roll stiffness will reduce the rate of camber change for a given load and thus limit the development of positive camber without increasing lateral weight transfer. This is the function of the device known as the camber compensator. One common type of camber compensator is a single auxiliary leaf spring, usually mounted underneath the differential opposite the transverse leaf assembly, pivoting freely in the middle at an attachment at the differential and connected at the ends to the vertical links out by the wheels. Thus, this style of camber compensator is actually a pure swing spring. By varying the length of the links connecting it to the swing axle vertical links, the "compensator" can be tuned to provide no preload and thus no added vertical stiffness at rest, or some preload to bias the compensator with droop stiffness at rest. Also, spring rate can be increased by substituting a thicker leaf.

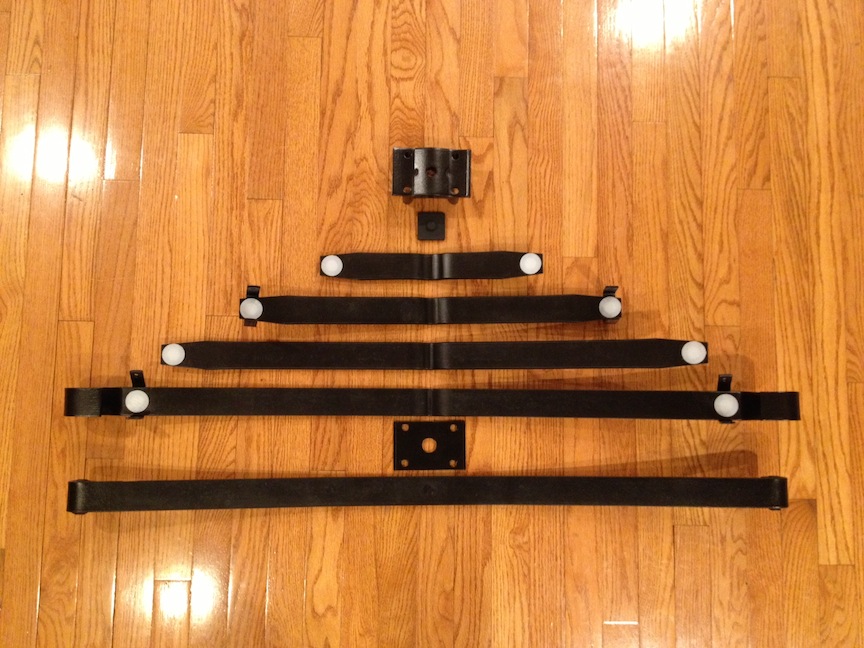

Leaf style camber compensator kits, based on the design first used on racing Spitfires in the 1960's before the advent of the swing spring, are available. Alternatively, you can custom fashion your own compensator assembly from a single spring leaf cut and drilled to size, a pair of anti-roll bar (ARB) links and some sheet steel for fabricating the center pivot and link connections. Such leaf spring camber compensator mechanisms have been used on other swing axle cars like the early Porsche 356 and VW Beetle and Chevy Corvair.

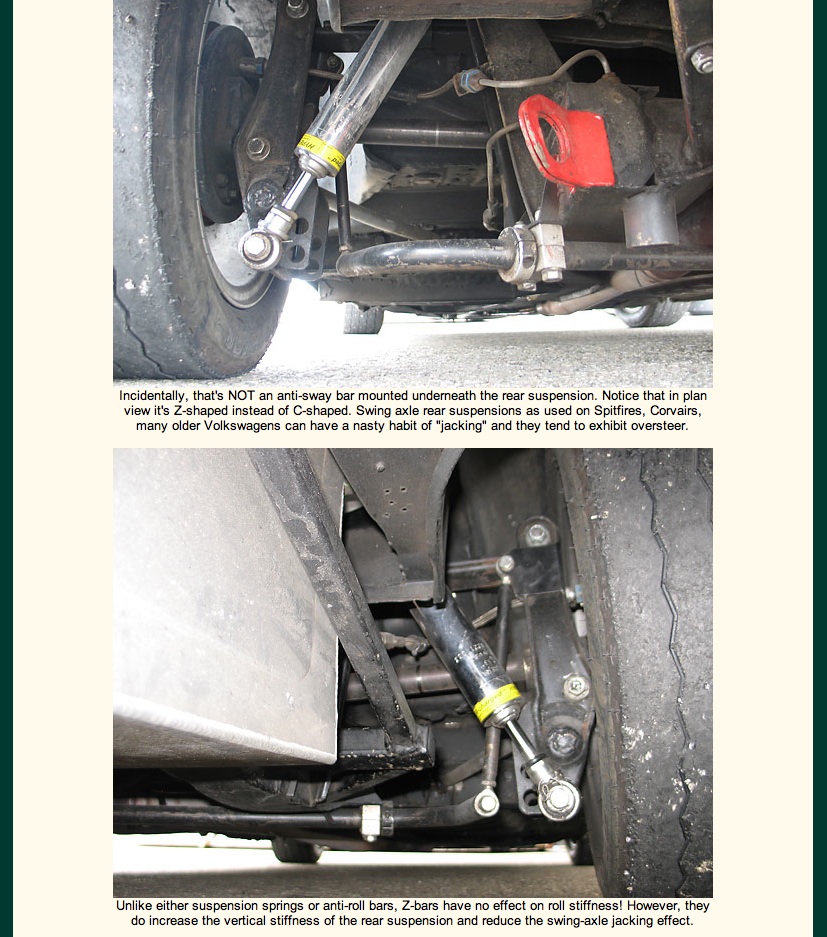

Another very effective device that provides vertical stiffness without adding any roll stiffness is the Z-bar. A Z-bar gets its name because it is "Z" shaped in plan view (in contrast to an ARB, which is "C" shaped). Note that Z-bars and other camber compensators, which add vertical stiffness without affecting roll stiffness, are the mechanical converse of an ARB, which adds roll stiffness without affecting vertical stiffness. Mounting a Z-bar requires adding two attachments--one on each side of the chassis--to hold the Z-bar (much like the way an ARB is attached), and an attachment point on each vertical link. The advantage of the Z-bar over the leaf-style device is tunability; its effective stiffness can be changed simply by changing where the links attach to its arms. See Pat Ryan's 1967 racing Spitfre for a tidy Z-bar installation:

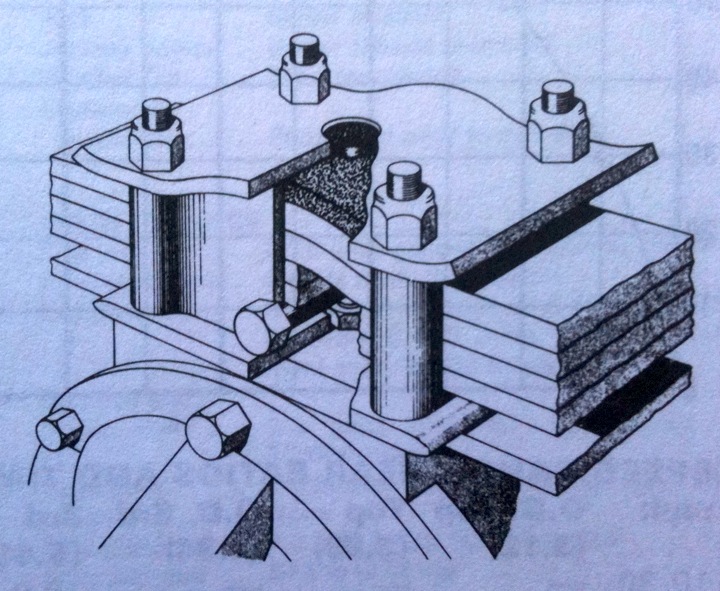

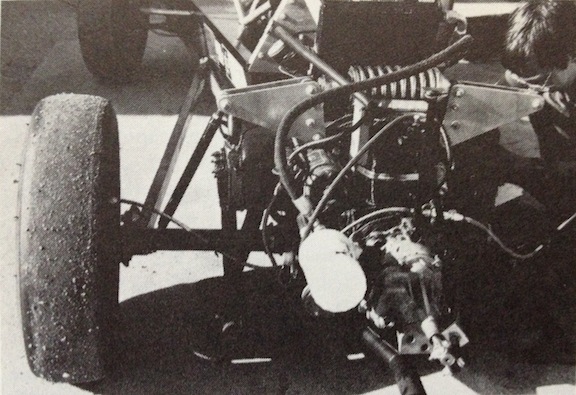

One other setup that simultaneously provides vertical stiffness and no roll stiffness is the single pivoting transverse coil spring arrangement. This is more complex and takes up more space than the basic transverse spring and camber compensator setup, and is impractical to implement in a street-going Spitfire. Here's a photo of such an architecture on a Formula Vee car:

A Z-bar or leaf style camber compensator is highly recommended for use with the earlier fixed springs, for safety’s sake if nothing else. Because the swing spring provides more vertical stiffness and less roll stiffness for less mass and complexity and better ground clearance than a fixed spring and camber compensator combination, replacing the fixed spring and front ARB with a swing spring and stiffer front ARB is a better performance option, but if for whatever reason (e.g., vehicle preparation rules) you use an early Spitfire fixed spring, install a camber compensator. A last fixed spring alternative is to go for significantly more vertical stiffness without regard to the downside of increased roll stiffness by using a much stiffer fixed spring, either by substituting one from another Triumph (e.g., replace an early Spitfire fixed spring with a GT6 mk1 fixed spring) or custom assembling/fabricating one.

A way to add even more vertical stiffness to a swing spring setup is to add a camber compensator. Another approach is to use the stiffer of the two swing spring models. Note that the much more common Spitfire swing spring, p/n 159640, has ~320 lbs/inch vertical stiffness, while the rare p/n 159654, used only on some of the later GT6s, has two thicker bottom leaves and ~380 lbs/inch vertical stiffness. This may be desired to achieve a particular ratio of front to rear vertical stiffness. However, for street use and the occasional autocross, a swing spring from a Spitfire or GT6 (with stiffer front ARB) works very well, even with a reasonably stiffened front suspension.

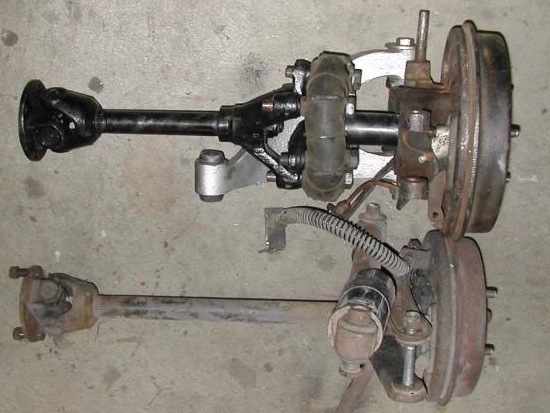

Longer Swing Axles

Longer swing axles are longer swing arms and therefore have a reduced rate of camber change for a given amount of suspension movement. They also widen the track to generate a slightly lower roll center and reduce lateral weight transfer. Moreover, using longer swing axles changes the angles of the vertical links, splaying them out and rotating them, reducing their vertical height and thus lowering the car slightly, which generating a little additional negative camber and lowers the c.g. Triumph fitted later swing spring equipped vehicles with swing axles measuring 1 inch longer; Spitfire mkIV's from February 1973 on, beginning with FH50001, all 1500’s and all swing axle GT6 mk3s were built with the longer swing axles. All else being the same, the results of switching from short to long swing axles are a 2-inch wider track, a roll center about 0.5 inches lower, lowering of the rear chassis and rear c.g. by about 0.2 inches, and about 0.7 degrees of additional negative camber. Longer swing axles are a performance improvement regardless of which spring setup is used.

Install Longer Swing Axles

Switching to long swing axles is a direct bolt-on to the later differentials in the mkIV and 1500, but not to the earlier ones in the mk1, 2 and 3. Because the early Spitfires using the short swing axles have differentials with smaller stub axle flanges, this requires either replacing the larger U-joint flanges on the longer swing axles with the smaller flanges from the shorter early swing axles or replacing the early differential and rear drive assembly with a later one (the early differential stub axles are slightly smaller than the later ones and do not swap). NOTE: Be sure to use longer radius arms with the longer swing axles to avoid generating too much rear toe-in. The early/short radius arms (p/n 133065) are about 12 5/8 inches long bushing-center to bushing-center and 1/4" shorter than the late/long ones (p/n 155930), which are about 12 7/8 inches long bushing-center to bushing-center.

A

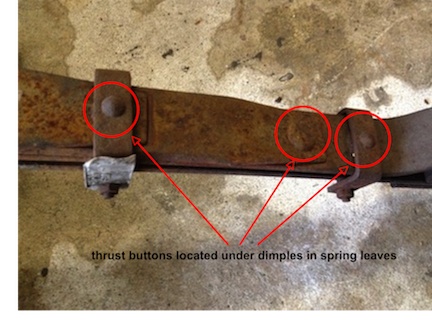

leaf spring needs to be in good order to be supple and work correctly.

The leaves need to slide freely against each other as the spring

flexes, which requires clean and smooth (not rusty) interfacing

surfaces with thrust buttons that are in good shape, and additionally

in

the case of the swing spring a pivot box rubber pad that is in good

shape.

If your rear end is actually too low or if the spring feels like it has

lost its compliance, cleaning the spring and renewing the thrust buttons

(and pivot box rubber pad too of a swing spring) are good measures.

Often a leaf spring is simply in need of maintenance and renewal, not

replacement and a trip to the recycler. Thrust buttons are little disks

captured in dimples at the ends of the

leaves and serve as bearing surfaces between adjacent leaves. There are

eight buttons in a Spitfire spring (same for the later swing spring and

the early fixed spring). The stock buttons are made of a rubber or

rubber-like material. By today they are often in bad shape in an

original spring, and in the case of a swing spring the outermost pair

are usually missing too.

The buttons need only be thick enough to barely separate the leaves at

the button locations. Spring arc and hence rear camber are

very

sensitive to leaf separation and therefore button thickness.

Typical and correct leaf separation at a properly functioning factory

button is only about a millimeter. Stock replacement buttons are

available from vendors, and these will deform in the spring after some

use from a cylindrical shape to a tiny broad-rimmed hat shape and reach

an equilibrium, and the arc of the spring and the ride height and

rear camber of the car will change and settle once the buttons stop

changing. This settling-in period bothers some people.

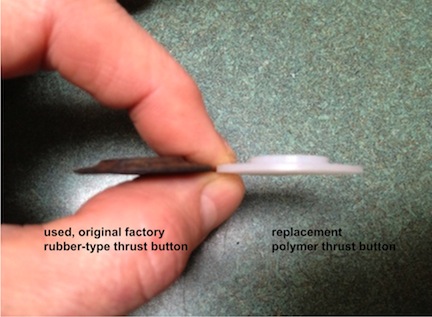

Alternative replacement buttons made of Teflon

are sold by some online vendors and some organizations (e.g., The

Dutch

Triumph Spitfire Club), but these typically have too tall a

profile and

will cause too much leaf separation. An option is to fabricate your

own, which is easy to do from 1 1/4" rod stock using common home shop

power tools. Personally I prefer a harder and more dimensionally stable

material than Teflon, and I have used ultra-high molecular weight

(UHMW)

polyethylene with success. UHMW polyethylene and other materials like

Delrin are impact resistant, durable and slippery like Teflon but don't

flow like Teflon. One nice advantage of using correctly-dimensioned

buttons made of these

materials is that a spring fitted with them is already at a new

equilibrium and requires no "break-in" or settling use time.

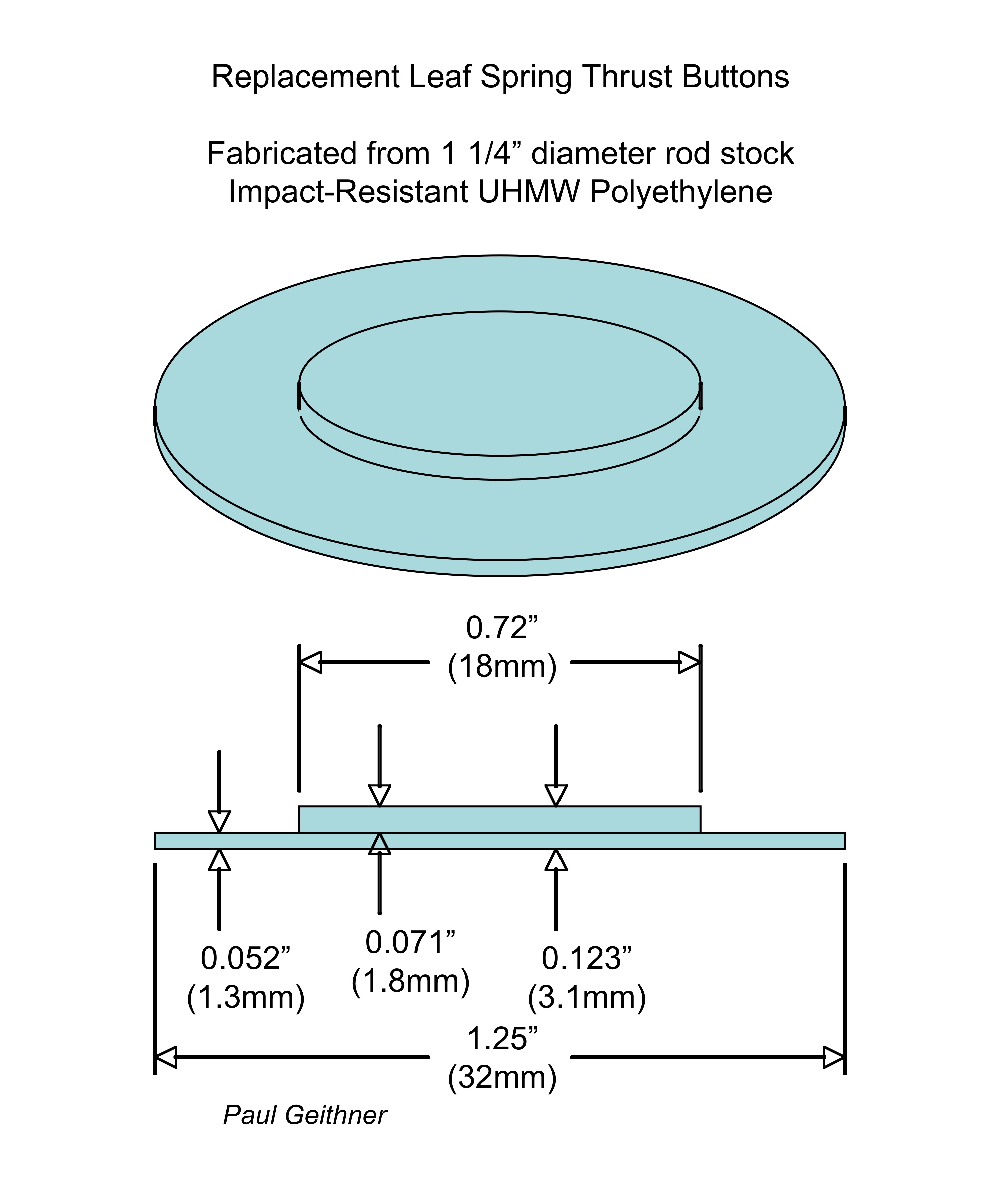

Below is an image of a new, uncompressed stock deformable

replacement button (p/n 114006) from Rimmer Brothers, photos comparing

an old original

factory button in its correctly compressed/deformed

functioning shape and a

replacement button that I made from 1 1/4" UHMW polyethylene rod stock,

and a drawing of the replacement buttons that I fabricate:

Button replacement is a good maintenance item and often a remedy for a

poorly performing spring, and is a much less expensive alternative to

buying

a whole new spring. Besides, unless the leaves have lost their temper

or have otherwise been severly damaged or broken, there's

no reason to replace

all that spring steel. To install new thrust buttons, simply remove the

spring assembly, disassemble, clean the leaves, replace the thrust

buttons and

reassemble. When the swing spring is unloaded, the outer-most pair of

buttons tend to fall out because the longest two leaves separate, so a

dab of the proper flexible adhesive in the dimples (e.g., 3M

Scotch-Weld 4693H) can help

keep these two buttons in place. Alternatively, wedging the

bolt sleeves of the outer pair of retaining straps is a way to keep the

ends of the last two leaves of the swing spring together and

the outer pair of

buttons captured when

the swing spring is unloaded.

Otherwise, a properly reassembled

spring with correctly dimensioned buttons will retain them and

function well.

Another maintenance item particular to the swing spring is the pivot

box, and especially its rubber pad. Old springs often have rusty pivot

boxes with compromised and ineffective rubber pads. The pad makes for a

properly-loaded pivot box and allows the floating leaves (the top four

with

the little hump in the middle) to rotate through small roll angles.

Replacement pads, available from vendors, are good and inexpensive

maintenance.

Some silicone or other 'dry' lubrication is not a bad idea for a

refreshed

spring. Although UHMW polyethylene and Teflon and Delrin are already

naturally slippery, lubrication will help the leaves slide freely and

reduce wear,

and using graphite powder or a non-greasy silicone spray type lube will

reduce friction and help

prevent corrosion without holding onto dirt like grease or oil can.

Note that button renewal may increase the arc of the spring and hence

raise the rear end, so reinstall the spring and settle the car,

remeasure rear camber and then fabricate and install a lowering block

if necessary to set the desired ride height and static rear camber.

Switch

the Rear Suspension Architecture

OK, after all that about swing axles, there is another small chassis Triumph rear suspension scheme that offers superior camber control and more tuning flexibility. Recall that swing axles are, by definition, both primary suspension links and drivetrain. A way to radically reduce a Spitfire's rate of rear camber change and lower the rear roll center is to eliminate the swing axles altogether and upgrade to a fully-independent multi-link rear suspension architecture in which the drive elements are not suspension links. Triumph achieved this with the "rotoflex" suspension it used on the GT6 mk2, a.k.a. GT6+, and early GT6 mk3 (rotoflex was used on the 2 liter Vitesse mk2 too but the GT6 parts are compatible with the Spitfire). Instead of swing axles, a lower wishbone plus a radius arm on each side serves as the primary lower suspension link. The transverse spring is the upper suspension element and a different vertical link houses the hub bearing. The drivetrain element is a two-piece shaft connected by an elastic "donut" that is stiff enough in rotation to transmit drive torque yet flexible enough orthogonal to rotation (i.e., along the direction of the shaft) to allow the assembly to vary in length (plunge and extension) and thus permit inboard and outboard motion of the wheels and proper suspension articulation.

This

last point is absolutely key, because one cannot simply add a lower

wishbone and keep the swing axles. In a fully-independent

multi-link suspension, the vertical links holding the hub

bearings

rotate on virtual swing arms that are much longer than the

distance to the differential, so they move on different arcs than swing

axles do and thus move inboard

and outboard relative to the differential with vertical motion. When

such a suspension is

used at the drive wheels, the driveshafts must be

able to vary in

length as well as tip and tilt at both ends or the whole linkage will

be over-constrained and cease to be a suspension.

The

rotoflex suspension has the distinct advantage of reduced camber

change, a lower rear roll center and greater tunability, but it

is much heavier than

the swing axle setup (about twice the weight), has a higher parts count

and is difficult to

maintain. The cast iron vertical link is rather massive and unsprung

(but some of the extra weight is due to the brakes being larger than a

Spitfire's). The lower wishbone is cast iron

and is partially unsprung, and the elastic rotoflex donuts are heavy,

mostly unsprung, prone to wearing-out and

difficult and expensive to renew. One

other note on this setup is that it has a 49 inch track (1 inch wider

than the "short swing axle" Spifires and GT6 mk1, but 1 inch

narrower than the "long swing axle" cars). So,

the GT6 mk2 rotoflex design is a

compromise. Given the swing axle's advantages in simplicity and reduced

parts count, low

cost, low maintenance and reduced mass, plus things like the swing

spring to compensate for its primary disadvantage, it's not a mystery

why

swing axles reappeared in the GT6 mk3 and persisted in the

Spitfire.

There

is one very good upgrade to the rotoflex design that addresses most of

its shortcomings, and that is to replace the rotoflex

driveshafts themselves with constant velocity (CV) joint

driveshafts. Canley

Classics has developed such a driveshaft, deriving it from

one that Triumph used in its front wheel drive 1500. The

Canley

driveshafts weigh less, are easy to install, have a smaller

envelope and require essentially no maintenance.

Canleys

also offers lighter weight alloy vertical links and aluminum wishbones

to significantly reduce mass (the wishbones are curved to clear the

rotoflex donuts, but CV driveshafts permit straight ones).

The

combined mass savings of the Canley driveshafts, alloy vertical links

and aluminum wishbones is roughly 5 kg per side, reducing total

mass of

the setup by about 25 percent and splitting the difference in mass

between the rotoflex and swing axle setups:

GT6 mk2 rotoflex setup = ~20 kg one side (includes brakes and radius arm)

Spitfire swing axle setup = ~11 kg one side

Canley setup with Canley driveshafts, alloy links and aluminum wishbones = ~15 kg one side

Switching

from swing axle to rotoflex-type rear is not a bolt-on but sort of

close to it. First, brackets for linking the wishbones

to the frame must be welded to the frame as on the GT6 mk2. Canleys

sells brackets with three different pairs of holes for tuning

the suspension geometry (specifically, this changes the angles

of the wishbones and varies the lengths of the virtual swing arms and

therefore changes the rates of camber change and relocates the roll

center). Second,

the rotoflex donuts are so large that they interfere with regular

Spitfire dampers running from

the vertical links to the chassis. A different,

longer rear damper specific

to the GT6 mk2 must be employed and an upper attachment for them must

be welded

to the

tub in the wheel well. However, if the Canley CV axles are used

then regular Spitfire length dampers

will clear and can be used and attached as usual. Third,

the ends of the brake lines run differently on the smaller Spitfire

rear brakes versus the

larger GT6 rear brakes, so some plumbing modifications must be made.

Fourth, rear roll stiffness is not the handicap that it is with swing

axles, so it's not so detrimental to use a fixed transverse spring

(rotoflex

GT6's and Vitesse's had fixed rather than swing springs). Lastly,

different

radius arms and mountings need to be used. GT6 mk2

radius arms are adjustable in length and are attached further inboard

on the GT6 mk2 tub heelboard than on the Spitfire. The inboard

location puts the trailing arm inner pivot in line with the inboard,

frame-mounted pivot point of the wishbone so that the

combo of wishbone and trailing arm becomes one large triangulated

articulating A-arm

assembly. So, new radius arm mounts need to be

welded to the tub heelboard as in the GT6 mk2 configuration. An

alternative is to substitute an entire GT6 mk2 frame for a Spitfire

one, which is more practical when doing a complete rebuild, but at the

very least new inner radius arm attachments still have to be

installed on the Spitfire tub. I'm doing precisely

this to produce a modified "roundtail" early Spitfire-bodied

version of a GT6 mk2. Paul Tegler has documented

a

discussion

of this conversion applied to his highly-modified '75

Spitfire.

Install

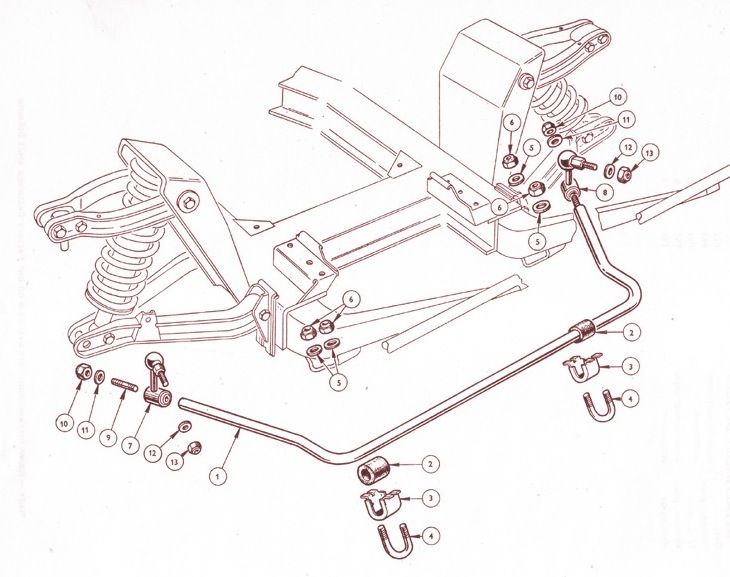

a Stiffer Anti-Roll Bar

Now,

moving on to the topic of anti-roll bars (ARBs), also called anti-sway

bars. If

you want to add more roll stiffness without adding vertical stiffness,

then you can add anti-roll bars. ARBs

are simply torsion

springs that

act only when the car rolls. A

thicker bar is a stiffer bar, and a little goes a long way because stiffness

goes with the 4th power of

bar thickness. The

swing spring Spitfires have

a 7/8 inch diameter front ARB, but an

aftermarket 1 inch

bar is

1.7 times stiffer; the fixed spring Spitfires have a 11/16 inch bar,

but a stock

7/8 inch

Spitfire 1500 bar is 2.6 times stiffer. All else being equal,

increasing roll

stiffness by means of a thicker front ARB will bias roll

stiffness toward the front and tend to make a car understeer more. However, on a Spitfire, installing a

thicker front ARB may not result in too much understeer. The

added front roll stiffness and consequent tendency to understeer

is offset somewhat by the

improved geometry of the suspension and tire contact due to reduced

body roll during cornering. See my table of

Spitfire and GT6 spring

and wheel rates to see how different front ARBs contribute to

vehicle roll stiffness.

Adding rear roll stiffness by fitting a rear ARB is typically not a wise idea on a swing axle car because it exacerbates jacking (note that although it is not disastrous to use a rear bar on a Spitfire equipped with a swing spring, it negates one of the advantages of the swing spring over the fixed spring). This is why zero-roll stiffness devices that add vertical stiffness to limit camber change, like Z-bars and leaf-style camber compensators, have been applied to various swing axle cars for decades. In fact, an ARB, which adds roll stiffness without affecting vertical stiffness, is the mechanical converse of a camber compensator, which adds vertical stiffness without affecting roll stiffness. Reducing or precluding jacking and controlling rear camber change are paramount objectives of swing axle control.

If

switching to a multi-link independent rear architecture like the

rotoflex, then adding a rear ARB is an option, and keeping a thinner

bar up front is OK. The point here is that the multi-link

independent rear

offers more flexibility

of tuning with ARBs in that both front and rear bars may be employed

and tuned

separately to

achieve a wide range of roll stiffnesses and front to rear roll

stiffness biases.

Sometimes ARBs are unintentionally preloaded on one end or the other because they are not flat and/or the mounts on the frame rails are not plane parallel with the A-arm attachments. The result can be a Spitfire that leans to one side or the other due to the jacking effect of the asymmetric preload. A way to eliminate this and set the ARB to zero preload at rest is to replace the factory ARB links with adjustable length ones and adjust them. Jon Wolfe sells adjustable ARB link kits, or you can kit your own from rod ends, jam nuts, spacers and bolts.

Install

Good Dampers (Shock Absorbers)

Dampers, also called shock absorbers, are critical to the dynamic behavior of the car, i.e., the nature of the car while it is moving and in transition from one suspension "set" to another, like when the car is initiating (entering) or completing (exiting) a turn or going over bumps and dips. Damper settings have a significant effect on ride and handling. Whereas force from linear springs is proportional to displacement, i.e., the amount of spring compression (spring force = spring rate * compression distance), viscous dampers exert force proportional to the speed of displacement (damper force = damper piston velocity * damping coefficient).

How Dampers Affect Handling

The right amount of damping makes a big difference in handling. Too little damping causes the car to oscillate after hitting bumps or changing directions. This makes it difficult for the driver to provide the right steering input at the right times and therefore makes the car difficult to control. Moreover, the car can oscillate so much as to lose contact with the road, resulting in loss of control. Too much damping and the car becomes too rigid in transition and the slightest bump or steering input causes one or more tires to lose contact with the road, also resulting in loss of control. A good damping ratio for a sporty car is around 0.3 (the ratio of the actual damping coefficient to the critical damping coefficient of the spring-and-mass system). If you change to stiffer springs and have adjustable dampers, don't crank up the damping too much. The right amount of damping varies as the square root of spring stiffness because critical damping is proportional to the square root of spring stiffness, so to maintain a given or optimum damping ratio, the amount of damping should be changed in proportion to the square root of stiffness. Premium dampers can be adjusted in both the bump (compression) and rebound (droop or extension) directions--sometimes independently, and bump and rebound damping affect handling in different ways.

Bump

damping affects the corners of the vehicle being loaded and is used

primarily to control the motion of the unsprung weight of the vehicle

(wheels and tires, hubs, and portions of the suspension links, springs

and drive axles). Bump damping adjustments should not be used to

control the downward movement of the vehicle when it encounters dips,

nor should it be used to control roll or bottoming. The ideal bump

setting for a vehicle can occur at any point within the adjustment

range of the dampers and depends on many variables. This setting is

when "side-hop" or "walking" in a bumpy turn is minimal and the ride is

firm and responsive but not uncomfortably harsh. Any additional bump

damping beyond this ideal setting and the "side-hopping" condition will

be problematic and the ride may be too harsh. If there is too

much bump damping at the front, then upon hitting a bump the whole

front of the vehicle--both the sprung and unsprung weight--will move

upward, reduce or lose contact with the road and "walk" off the road

first, resulting in understeer. Similarly, if there is too

much bump damping at the rear, then upon hitting a bump the whole rear

of the vehicle--both the sprung and unsprung weight--will move upward,

reduce or lose contact with the road and "walk" off first, resulting in

oversteer. However, sufficient front bump damping is useful for

reducing corner entry understeer, and likewise sufficient rear bump

damping is useful for reducing corner exit oversteer. Clearly,

an optimum "Goldilocks" setting is desired.

Rebound

damping affects the corners of the vehicle being unloaded and is

used primarily to control transitional roll behavior, i.e., how the

vehicle leans when entering and exiting a turn. Remember that dampers

do not limit the total amount of roll but rather control the rate of roll, or

much time it takes the vehicle to achieve a given amount of

roll. Total, steady-state roll is determined by other things

like the stiffness of the springs and anti-roll bars and the locations

of the roll centers and center of gravity (c.g.), etc. Too much rebound

damping on either end of a vehicle can keep the suspension from

extending fast enough to keep the tires in good contact with the road

and so cause an initial loss of grip, which will make the vehicle

oversteer or understeer excessively when entering or exiting a

turn. Specifically, rebound damping at the rear affects corner

entry because the vehicle is decelerating and weight is being

transferred from rear to front during corner entry, so too much rear

rebound damping can lead to corner entry oversteer. Rebound damping at

the front affects corner exit because the vehicle is accelerating and

weight is being transferred from front to rear, so too much front

rebound damping can lead to corner exit understeer. Thus rebound

damping adjustment can also be used to help tune the way the vehicle

behaves entering and exiting corners. Moreover, too much rebound

damping in relation to spring rate will cause a condition known as

"jacking down," wherein after the vehicle hits a bump and the spring is

compressed, the damper prevents the spring from returning to a neutral

position fast enough before the next bump is encountered, which

compresses the spring some more and so the whole vehicle falls or jacks

downward. This can repeat with each subsequent bump until the car is

lowered onto the bump stops. Contact with the bump stops causes a

sudden and drastic increase in suspension stiffness, upsetting the car

and resulting in a loss of contact and grip. If this condition occurs

at the front, the car will push/understeer; if it occurs at the rear,

the car will get loose/oversteer.

Damper Dimensions

For street use, you can use the stock variety of dampers, even if you modestly increase the stiffness of the springs. They won't be ideal if you stiffen and lower the car, but they are the least expensive way to go. However, beware the dimensions of some Spitfire dampers sold as stock replacements. Some such front dampers have spring seats that are too high, i.e., the distance between the center of the lower A-arm mounting and the lower spring seat is 3.875 rather than 3.25 inches. Using such dampers will cause the front end to sit noticeably too high, resulting in a higher c.g., suboptimal suspension geometry and poor handling:

Furthermore, some replacement front dampers have long bodies or less useable piston rod length that yield inadequate bump travel when used in a lowered setup (e.g., Gaz, which unfortunately sit on their bump stops when used in the 1 inch lower-than-factory setup). Also, beware the compressed length of some rear dampers sold as stock replacements. The fully compressed length of rear dampers grounded on the bump stops should be no more than 9.5 inches (eye center to eye center), not 10.5 inches like some "stock" replacements. A Spitfire with 3 to 4 degrees negative rear camber will have rear dampers compressed to about 10.5 inches, so fitting such incorrect dampers leaves no rear bump travel, resulting in poor handling and noticeable oversteer. The remaining approximately 1 inch of damper bump travel afforded by correctly-dimensioned rear dampers is necessary and translates into about 1.6 inches of tire bump travel due to the rear suspension geometry:

Damper Options

Premium adjustable dampers (e.g., Koni) will allow you to tune the car's handling characteristics. Some allow damping adjustments to be made in situ with the turn of a knob. Some front dampers have adjustable coil spring seats for changing ride height without changing the springs, making fine tuning of ride height simple and easy. As mentioned previously, it is best to use short bodied dampers on a lowered and stiffened setup to allow more bump travel than standard length dampers. Good front damper alternatives are ones that fit the Ford Mustang II, like the QA1 MS303 and the Pro Shocks ASBSR3AM2TP. These afford about 3 inches of total damper travel, i.e. about 6 inches of total front tire travel, divided roughly equally between bump and droop in the 1 inch lowered geometry. Another benefit of short bodied front dampers when used with springs as short as 9 inch free length is that the springs will not go slack at full droop.

As with front dampers, it is good to use short bodied dampers on a lowered rear suspension to afford more bump travel. Good alternatives are the non-adjustable Pro Shocks SM-401 and the adjustable Spax KSX series GDA4011SPAXLOW (offered specifically for lowered small chassis Triumphs). Both have about 8.75 inches compressed length vs. the typical standard 9.5 inches and nearly 4 inches of damper travel, i.e., about 6 inches of total rear tire travel.

When adjusting dampers, start by setting them to fully soft, then go through cycles of driving and adjusting until the handling is best/times are fastest. Here's how to adjust dampers that have single combined bump and rebound adjustment (adapted from Spax):

Initially set all dampers to fully soft. Then adjust up in four (4) click increments and drive. Every time the driving sensation improves, carry on adjusting up by four (4) clicks. Every time the driving sensation becomes worse, adjust down by one (1) click.

Here's how to adjust dampers that have separate bump and rebound adjustment (adapted from Koni):

COMPRESSION

(BUMP): Adjust bump damping first, before adjusting extension

(rebound)

STEP

1: Set all four dampers on minimum bump and minimum rebound settings.

STEP

2: Drive one or two laps to get the feel of the car. Note: When driving

the car during the bump adjustment phase, disregard body lean or roll

and concentrate solely on how the car feels over bumps. Also, try to

notice if the car "walks" or "side-hops" in a rough turn.

STEP

3: Increase the bump setting three (3) increments on all four dampers.

Drive the car one or two laps. Repeat this step until a point is

reached at which the car starts to feel hard over bumpy surfaces.

STEP

4: Back off the bump adjustment two (2) increments. Note: The back off

point will probably be reached sooner on one end of the vehicle than

the other. If this occurs, keep increasing the bump on the soft end

until it, too, feels hard, and then back it off two (2) increments.

Bump damping is now set.

EXTENSION

(REBOUND):Adjust rebound damping only after setting bump

damping

STEP 2: Increase rebound damping three (3) increments on all four dampers and drive the car one or two laps. Repeat this step until the car enters the turns smoothly (no drastic attitude changes) and without leaning excessively. An increase in the rebound stiffness beyond this point is unnecessary and may result in a loss of cornering power. Note: As with the bump settings, this point will probably be reached at one end of the car before the other, so keep adjusting the soft end until it feels smooth and does not lean too much. Rebound damping is now set.

Ensure Good Brakes (a.k.a., before you go, make sure you can STOP!)

The final segment here under handling is braking. Brakes are of course important for safety, but good braking is key to good handling and crucial to making a car faster if you want to do more than just go in a straight line. Besides, fast effective braking is fun! Braking is simply the conversion of the kinetic energy of motion into waste heat energy. Braking force is the product of the coefficient of friction of the braking material and caliper piston force, and piston force is proportional to total caliper piston area, so larger calipers with more total piston area and pads with higher coefficient of friction material will improve braking. Brake effectiveness is also dependent on the ability to eliminate or dump waste heat, so bigger rotors, vented rotors and larger pads will dissipate heat better and yield better braking with less fade. Spitfire brake components in good working order make for adequate braking, but there is a range of enhancement options to consider. The simplest and most significant change you can make for the better with the stock setup is to use premium brake pads. Mintex, Hawk and Porterfield brand pads are good upgrades. Another easy and relatively inexpensive upgrade is to replace the stock rubber flex lines with less complaint ones, typically covered in braided stainless steel. The stock flex lines connecting the hard lines on the frame to the brakes on the suspension swell a little bit under pressure. Replacing them with less compliant ones will transfer more braking force faster to the brakes, improving performance and feel. There are many alternative hardware options for further enhancing braking. One relatively easy and essentially bolt-on upgrade is to install GT6 brakes. GT6 caliper piston area, pad area and rotor area are all greater than that of Spitfire brakes. Swapping front brakes involves substituting GT6 vertical links, spindles, hubs, wheel bearings, rotors and calipers for the Spitfire parts (everything outboard of the A-arms); you can't substitute just rotors or calipers due to component compatibility. The rear drum brakes of the GT6 are larger too, and these parts can be substituted as well, but this is not as important and not absolutely necessary. Because the process of braking transfers weight to the front, the front brakes do most of the braking and are most important. Another, nearly bolt-on upgrade that is readily available and relatively inexpensive is to install GT6 hardware but use '79-83 Toyota pick-up truck front brake calipers (you can modify the following adaptation of Toyota brake calipers to TR Triumphs for fitment to the Spitfire). Make sure your wheels will accommodate the larger GT6 or Toyota calipers without interference. Lastly, there are several, albeit relatively expensive, aftermarket brake kit options using parts from manufacturers such as Alcon, AP and Wilwood that can significantly improve brake performance.

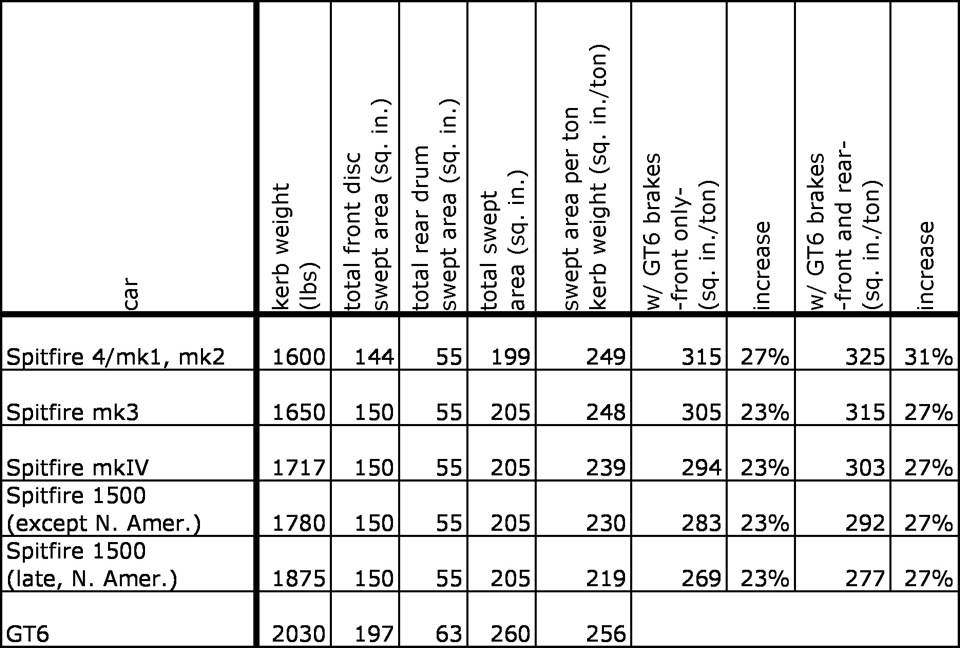

Handy metrics of braking capability are total swept area of braking surface and swept area per ton of vehicle weight. Typically the greater these values, the better the braking. The greater the swept area, the more fade resistant the brakes are likely to be, and the greater the swept area per ton, the shorter the braking distance is likely to be. Early Spitfires (Spitfire 4/mk1 and mk 2, which have 12P front calipers) have 199 sq. inches of total swept area (144 sq. inches front discs and 55 sq. inches rear drums) yielding around 249 sq. inches/ton. Later Spitfires (those with 14P calipers, i.e., mk3, mkIV and 1500) have 205 sq. inches of total swept area (150 sq. inches front discs and 55 sq. inches rear drums), yielding 248 sq. inches/ton (mk3) to 219 sq. inches/ton (late U.S. market 1500). For comparison, upgrading to GT6 brakes leads to 260 sq. inches swept area (197 sq. inches front discs and 63 sq. inches rear drums) and makes possible 325 sq. inches/ton on the earliest Spitfires (31 percent increase) to 277 sq. inches/ton on the late U.S. market Spitfire 1500 (27 percent increase). The results are summarized in the following table:

For

more insight and information on vehicle handling and suspension

design, check out:

How to Make Your Car Handle, by Fred Puhn

Tune to Win, By Carroll Smith

Power = Torque * angular velocity [note: this is a scalar product]

= Torque * 2*pi * rotational speed

When using the Imperial units foot-pounds for torque and horsepower for power, and using RPM (revolutions per minute) for rotational speed, the equation becomes:

hp = ft-lbs * RPM/5252

In the SI units of Newton-meters for torque and kilowatts (kW) for power, this becomes:

kW = N-m * RPM/9549

Other handy relationships are:

1 hp = 746 watts, 1 kW = 1.341 hp: multiply hp by 0.7457 to get kW; multiply kW by 1.341 to get hp

1 ft-lb = 1.356 N-m, 1 N-m = 0.7376 ft-lbs: multiply ft-lbs by 1.356 to get N-m; multiply N-m by 0.7376 to get ft-lbs

1 RPM = 1/60th Hz; 1 Hz = 60 RPM: 6000 RPM = 100 revs per sec (100 Hz) = 1 rev every 10 milliseconds = 36 crank degrees per millisecond

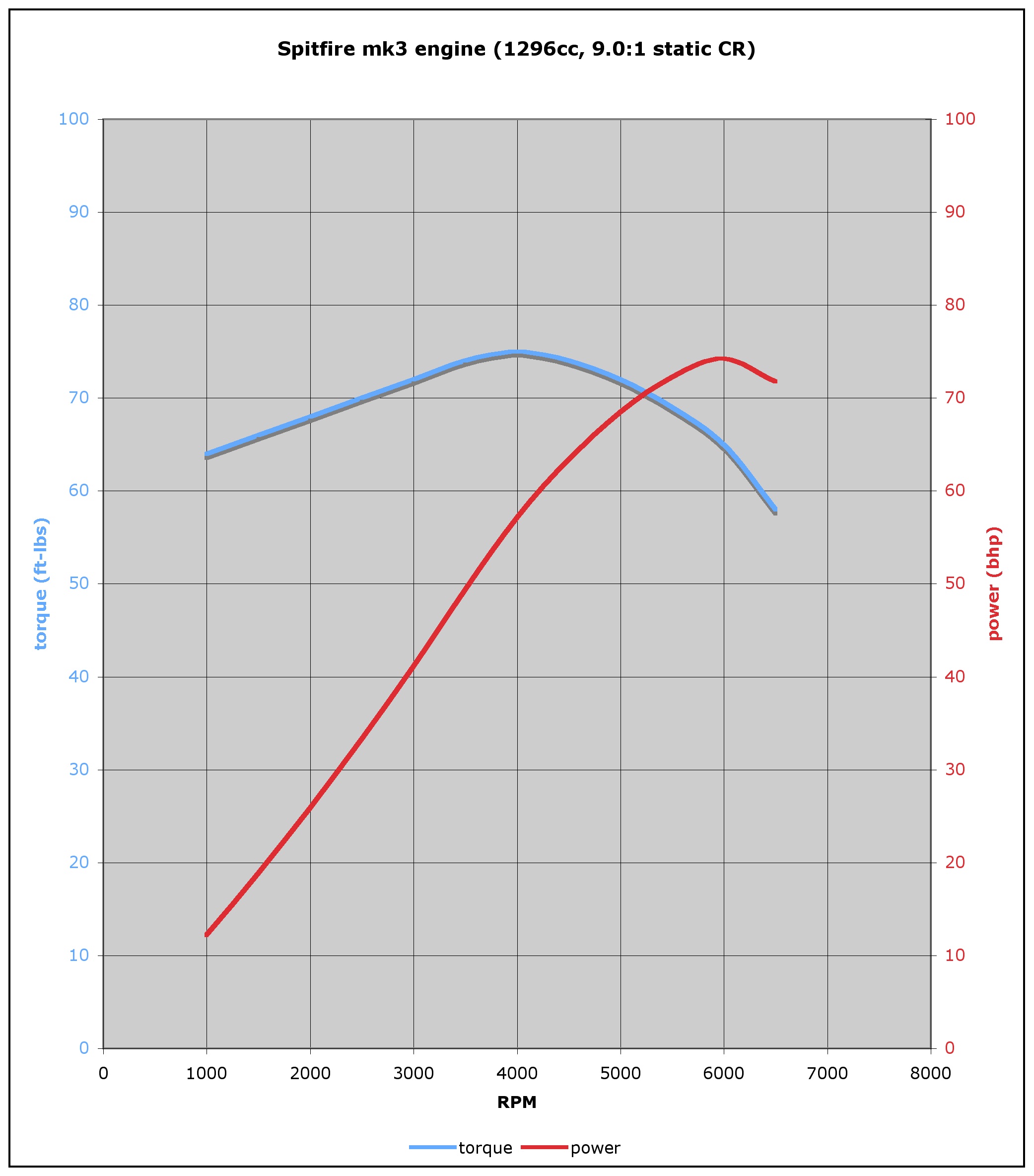

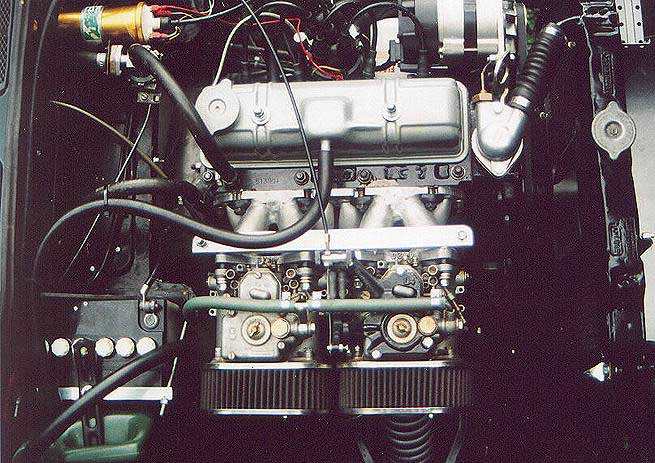

Spitfires came with basically four different engines--all variations on the same Standard-Triumph model inline-four, three main-bearing, pushrod-actuated overhead valve engine. Spitfire 4, mk1 and mk2 models came with 1147cc displacement units, mk3 and mkIV models came with two versions of the 1296cc or "1300" engine (the "small journal" models in the mk3 and "large journal" in the mkIV) that are basically bored-out versions of the 1147, and the 1500 came with the 1493cc or "1500" engine, which is essentially a stroked large journal 1300. There is further differentiation through the use of different cylinder heads and camshafts. The 1147 and small journal 1296cc engines have the lightest crankshafts and can spin up to the highest RPMs, and the small journal 1296 is popular with racers. The large journal 1300 and especially the 1500 have the heaviest cranks and flywheels of the bunch and so don't lend themselves to running as high RPMs as the small journal engines. However, the 1500, being longer stroke, produces more low RPM torque and is a perfectly adequate engine for a street Spitfire.

The purpose of the drivetrain is to apply torque from the engine to the drive wheels and tires. Unlike DC electric motors, which develop max torque at zero RPM that decreases from there, internal combustion engines produce max torque at a mid level of RPM and produce reasonable levels of usable torque over a range of RPM, so some gearing is a good idea. Gearing simply is a way to apply different amounts of leverage to make the most use of the torque and power from the engine to make the car move effectively. Gearing "transforms" torque, but not power. A 'low' gear, like the 3.75:1 first gear in a Spitfire mk3, multiplies the torque from the engine 3.75 times but reduces the speed of rotation 3.75 times (divides by 3.75) and so power is unchanged (neglecting frictional losses). The final drive multiplies torque again, by 4.11 in the Spitfire mk3, to deliver it to the wheels and tires for application to the ground. The 'low' gear (high leverage ratio) allows the engine to rev up quickly and operate near peak power where it can deliver a lot of torque most quickly and do the most work with the car at zero or low speeds. As vehicle speed increases, the gears are changed to higher ones (lower ratios) to allow the engine to continue to work at high revs where its power is greatest and it can make the car accelerate as much as possible. The ratios and "spacing" of the transmission gears and final drive, the strength of all the elements and frictional losses in the drivetrain are also important factors determining quickness and reliability.

If you are planning on using your Spitfire for a lot of highway driving, consider installing a transmission with an 'overdrive' unit or replacing it with a 5-speed transmission adapted from another vehicle (e.g., a Ford T-9) in order to have a top gear with a ratio of less than 1 to keep the cruising RPM down and reduce engine wear over time. Using a 3.89:1 final drive with an overdrive is a nice combination for street use that provides both quickness and reasonable RPMs for highway cruising. There's a weight penalty of about 26 pounds with an overdrive unit compared to no overdrive, but it's a fair trade. If you use a 4.11:1 final drive, the differential assembly in the late (FC120001 and on) Spitfire mk3 and 1972 North American Spitfire mkIV is the most robust with the same "large" output stub axles as those in the later 3.89:1, 3.63:1 and 3.27:1 units. These later final drives are the strongest, possessing the largest and strongest flanges, bearings and shafts all around.

The following equations relate road speed, engine RPM, gear ratio, final drive ratio and tire diameter:

vehicle speed (mph) = RPM*tire diameter (inches)/[336.1*gear ratio*final drive ratio], or

vehicle speed (kph) = RPM*tire diameter (cm)/[530.5*gear ratio*final drive ratio]

RPM = vehicle speed (mph)*336.1*gear ratio*final drive ratio/tire diameter (inches), or

RPM = vehicle speed (kph)*530.5*gear ratio*final drive ratio/tire diameter (cm)

James Carruthers has a nice gearing calculator on his "Mintylamb" site for comparing road speed and engine RPM for various gear ratios, final drive ratios and tire diameters.

Lose

Weight, i.e., "Add Lightness"

Many motorcycles can out-accelerate the hottest performance cars, even though they have much less power because proportionally they weigh even less such that the ratio of their power to their weight is much higher than that of most cars. The easiest and cheapest way to make your Spitfire feel more powerful is to shed mass and improve the power-to-weight ratio. As mentioned earlier under handling, this is easy to do on the later Spitfires in the U.S. by removing all the extra bumper and bumper reinforcing hardware they were burdened with.

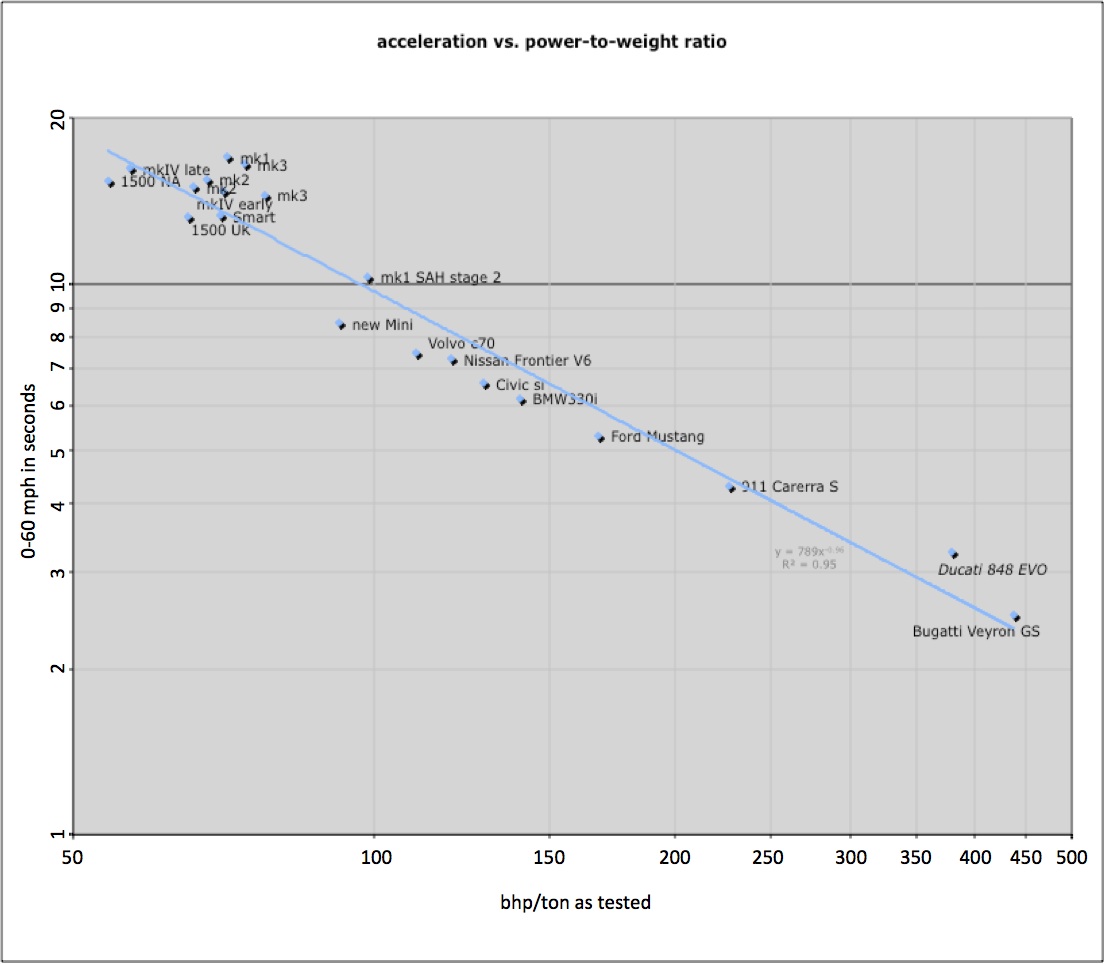

A good metric of performance is power per unit mass (or weight). Horsepower at the wheels divided by total test weight of the car is the ideal metric, but since wheel horsepower is typically not published information and has to be obtained on something like a rolling road that introduces additional variables, peak brake horsepower (bhp) is a good proxy for relative comparison purposes. Below is a plot of actual test data of Spitfires (from "Triumph Spitfire Gold Portfolio") and some assorted vehicles circa 2011 (from "Road & Track" test reports) spanning the range, from the 70 bhp Smart fortwo coupe to the 1001 bhp Bugatti Veyron Grand Sport supercar, plus the 119 bhp Ducati 848 EVO motorcycle for comparison. The trendline is a best-fit of the actual data (weights are as-tested and include driver weight), and given the mathematical relationship it is a straight line on a log-log plot. The point of the plot is to illustrate the relationship between acceleration and the power-to-weight ratio. The greater the power-to-weight ratio, the quicker the vehicle; each doubling of bhp/ton cuts acceleration time approximately in half: